#149: Unknown territory

PlayerUnknown has struggled with the making of his staggeringly ambitious new project. Things are finally looking up.

A couple of months ago I got an email from David Polfeldt, the former managing director of Ubisoft Massive and subject of a truly excellent instalment of Max HP, Hit Points’ subscriber-exclusive interview series. Since leaving Massive, David has reinvented himself as a game-biz consultant, and he was writing to tell me he’d just landed a new client. The company was working on something big and crazy; the founder wanted to talk about his experiences with it, and why he was bringing David on board to help out. He’d read David’s Max HP, and liked its style and level of detail (ah, flattery. Can’t get enough of it). Was I interested?

I was, cautiously, though naturally I needed to know more before I could commit. Was this someone I and my readers had heard of? Was it someone they’d be interested in hearing from? And was the project really as ambitious as it sounded?

Hahaha.

The first thing I notice about Brendan Greene is that the big beard is gone. The last time we saw the man better known as PlayerUnknown was in a Twitter video announcing his new venture, PlayerUnknown Productions, and he was a hirsute fellow indeed. When we meet on a video call in late July, however, he is back to the Brendan I recognise, his goatee closely cropped. As a man of generous facial foliage I am always somewhat disappointed when one of our number leaves the tribe. What happened?

“I grew it right up until that video was made,” he tells me. “I told my fiancée that I’d be growing it until I announced something. It took longer than I thought! Literally the day after the announcement it was back down to a goatee. It was getting hot, especially underneath, it was getting very sweaty. I didn’t like it.”

I resist the temptation to hang up on the spot. From the little that Brendan and his new partner in crime have told me about PlayerUnknown Productions, I know there’s an intriguing story here. And the gain and loss of the beard is a story in itself, portraying as it does someone who has perhaps been lost in the wilderness for a bit. Partway through our discussion I can’t help but ask if Brendan ever considered walking away from games; if he had ever considered following other creators of breakout, industry-shaking successes who have either lost their appetite for the work or are excessively burdened by the weight of expectations around what they might do next. They disappear off into the hills, never to be heard from again. Buy a big house, take bad drugs, grow out your fingernails like Howard Hughes, shitpost… and sure, why not, grow a big beard while you’re at it.

Brendan, it rapidly becomes clear, is not that sort of person. PUBG, he explains, was merely one step on a longer, far more ambitious journey; he always imagined the game would be much bigger and broader than it turned out to be, with battle royale just one of many game modes on offer. (That’s why it wasn’t called PlayerUnknown’s Battle Royale.) “I wanted to build this big open world, even before battle royale,” he says. “I was fascinated with this idea of digital spaces, places where there are no real rules but a set of systems that you can use — like DayZ, or the many ArmA mods. That fascinated me, and still does. I never considered just walking away.”

Moreover, he is quite clearly unburdened by other people’s opinions of him and his work. Expectations don’t really come into it. One of the recurring themes of our discussion is a sort of creative selfishness, though I do not mean that as a pejorative; it is a single-minded, obsessive passion for finding a way to a tremendously lofty goal, and I respect it enormously. “I’m making this thing for me,” he says. “I want to build this big digital place because I want to go there. If other people want to go there too then great, but I don’t really care what other people think.”

That’s a wonderful way to think about making something, I think. But it’s fraught with peril too — particularly when you’re trying to do something that’s never really been done before, on an unprecedented scale. And that is certainly Brendan’s intention.

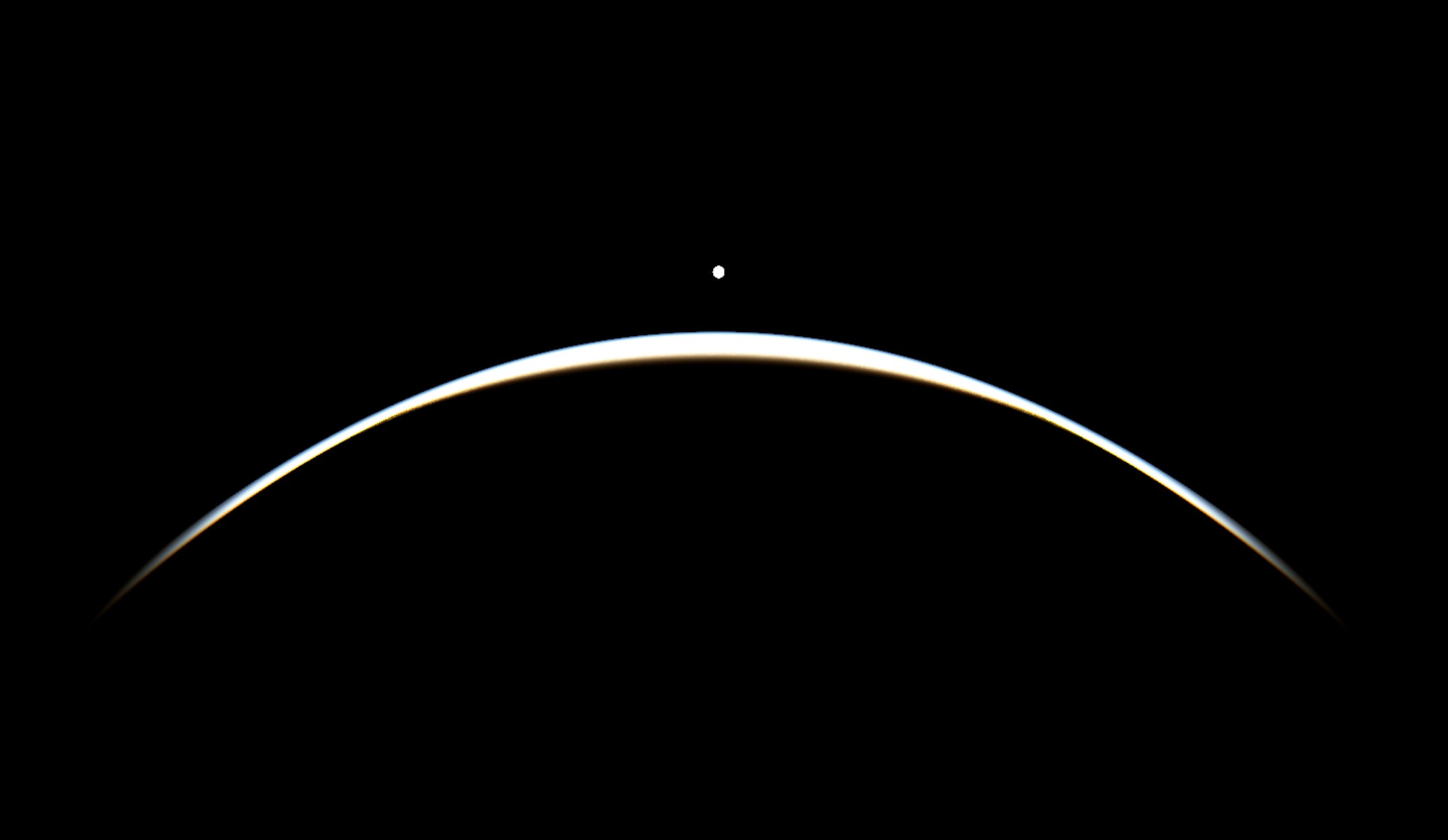

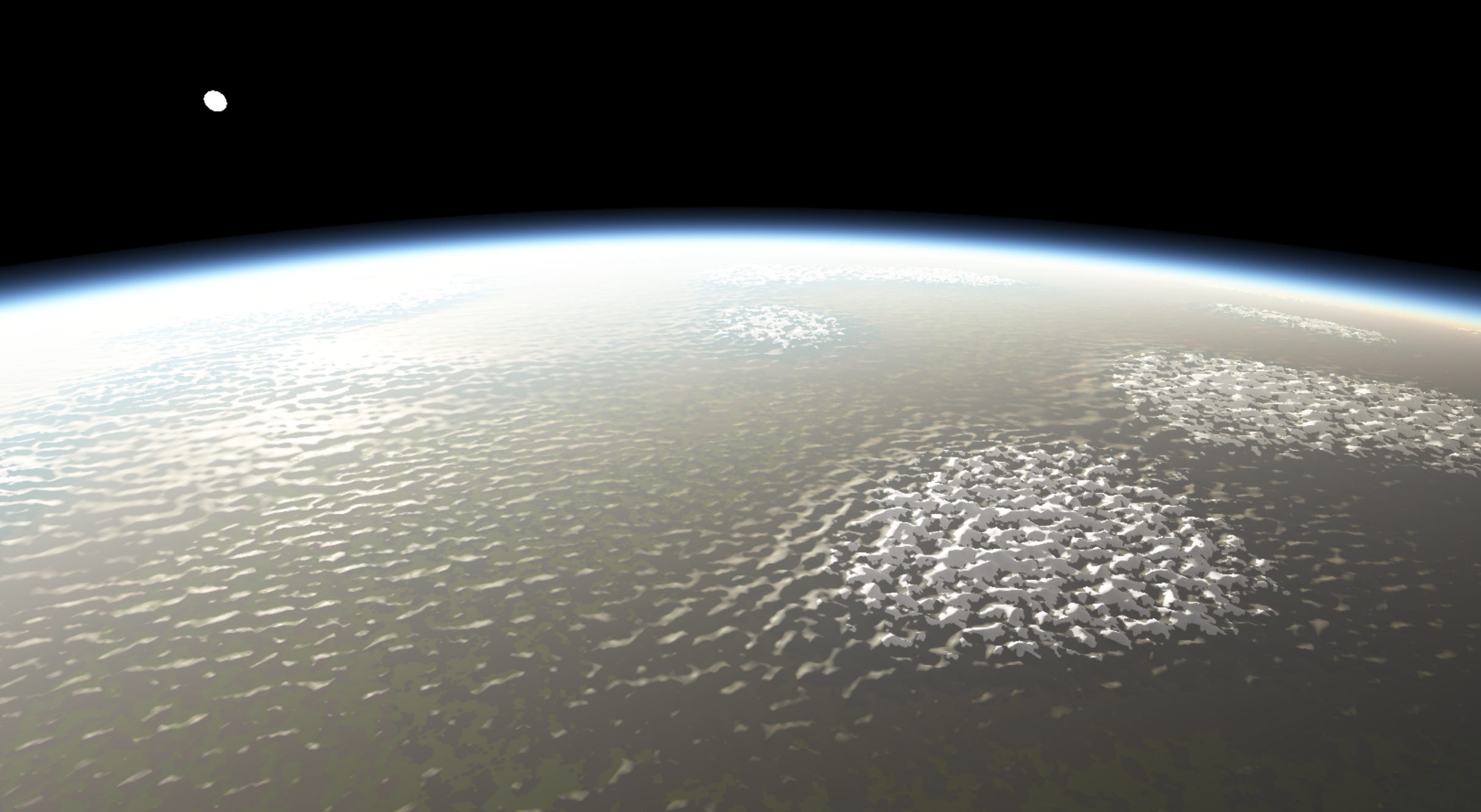

Brendan left the PUBG development team in 2019, and set up PlayerUnknown Productions in Amsterdam. The vision, laid out at length in this VentureBeat piece from last year, was (and remains) frightfully ambitious. The ultimate goal was Artemis, an Earth-sized virtual world in which hundreds of thousands of players would be able to make and play anything they liked. It would be built by a combination of talented developers, creatively engaged users and advanced machine-learning agents, and powered by the same technology PlayerUnknown Productions had used to build the thing in the first place (an engine named Melba, after the revered NASA mathematician Melba Roy Mouton). The first step on the road would be a tech demo called Prologue, a world 64 kilometres square, built with a combination of the studio’s own tools and Unity. It would begin life as a minimal survival game, and be progressively fleshed out over time.

And so this new studio, with a couple of dozen staff, set out not only to do something virtually unprecedented; it set out to do several of them at once. It promised a game, a vast world and an engine, all of them interdependent on each other and on the humans and machines that would be used to make them. Which is a bit mad, really, when you think about it. It is not entirely surprising to hear that the road has been a bit bumpy.

What does surprise me about it is how readily Brendan accepts the blame for it. In our initial email discussion he’d acknowledged that many of the studio’s problems were caused by his lack of management experience. This confused me a little. I knew his origin story — a thoroughly atypical one; he’d been a photographer and DJ living in Brazil until he got into modding — didn’t exactly paint a picture of an experienced leader. But surely Brendan was no stranger to managing teams? He’d headed up the making of PUBG, after all. But the creative director’s role is largely about setting goals, not necessarily reaching them — and when your name is in the game’s title, your job description inevitably shifts away from the norm.

“When we first started on PUBG, we were a small team. There were about 30 of us,” he tells me. “I had a very good lead game designer, and I gave general instructions for what I wanted in the game. Then once we hit early access, I went on the road, doing the press tour. And I didn’t come off the road, really, until we launched the full game. In that time the team grew, and I didn’t have a lot to do with the day-to-day because I just wasn’t there. It was very hard to keep me up-to-date on what was happening, so I didn’t get a lot of management experience.”

When he started PlayerUnknown Productions, Brendan admits he was “batting blind”. He knew what he wanted to make, and was comfortable setting what he thought were the goals the team needed to get there. But there’s a huge difference between giving creative guidance to a small, established team, and actually building a team in a project’s image — particularly one so unconventional as this. “I just employed the wrong people,” he says, making clear that this was a failure on his part, rather than anyone he hired. “I don’t want to throw anyone under the bus at all; it was more that I didn’t know what I was looking for. If you haven’t been in the trenches for many years, there’s just a lot you don’t know. Making games, I have a general idea of what’s needed — but I don’t know what to look for in a technical director, or an art director.

“And this is where I’ve got into trouble: I brought people on who were not right for the job. They’re all great at what they do, but I put them in the wrong position. We ended up losing a lot of people over the last two years or so where we’d get in a great lead and everyone would think the game was great, but they weren’t making the game that I wanted. I wasn’t explaining it well enough.”

This rate of staff turnover sits firmly at odds with Brendan’s vision for the business. “My aim has always been to build this authentic studio, that’s kind of humble: we want to make good things, and hope that players like them. I want to be fair to my employees. I want to give them a space that’s safe, where they want to come to work.” Covid-era remote work is very different in the Netherlands to, say, the US: houses are smaller, and staff have been working on kitchen tables and in attics. “It’s important to me to be able to provide a space that people really enjoy coming to,” he says. He’s spent his own money making the office a pleasant, comfortable place to be; that doesn’t count for much if recruitment is a revolving door.

Hence the arrival of David, who Brendan met at a conference over the summer. The former MD of Ubisoft Massive has seen this sort of thing plenty of times in his several decades making games; times when, whether through errant recruitment or poor communication, there’s been a gap between the goals that are set by leadership and the team’s interpretation of them. Often, development staff will see it as their job to fill that void: to “translate this vision into something that works,” as David puts it. “So suddenly, what you have on the production floor isn’t the purest possible interpretation of the vision. I love dreamers, and optimists, and people who think everything is possible. But it’s really important to understand their vision.

“I’ve not been with the studio for long, but I think this is where I can really help. I have zero issues with the vision — in fact I think it’s better than Brendan thinks it is, because it’s more cohesive than he gives himself credit for. All we need to do now is form a team around that vision and make people understand it, without a disconnect that leads to people making their own interpretations of it.”

That vision, however, has also shifted a little — if not in terms of the ultimate destination, then certainly in the journey. Using Unity was supposed to speed things up, enabling the team to release Prologue to give players a taste of what the studio was building towards while developing the engine and Artemis behind the scenes. That birthed an experiment which the team called Daedalus: a DLL plugin that generated a 64km by 64km world, populated with trees and artist-made locations, at runtime within Unity. “I thought we could build an engine and develop a tech demo at the same time,” Brendan says. “That wasn’t a great idea. The tech team was kind of split between trying to get the DLL working and trying to plan out and build an engine.”

Earlier this year the team decided to abandon Unity. They realised that there was no way to shortcut the making of Prologue, since it and Artemis were effectively the same thing, albeit on a vastly different scale. “Currently gaming is trapped within these kind of 20km by 20km boxes,” Brendan says, “because that’s how much you can reasonably make with a large team of artists in five years.” The work required to generate and populate a 64km by 64km world, in other words, is the same as generating and populating a planet-sized one. Both are clearly too big for human labour alone, and the solution to the smaller problem can surely solve the bigger one as well.

“I often say that it’s like we’re building a combustion engine in the age of horses,” Brendan says. “People know how to breed horses and train them to run faster, but that doesn’t scale.” A horse is never going to break the sound barrier, or go to the moon. Today’s triple-A open-world developers are thoroughbreds, the best there has ever been at running in a straight line to an established goal. Over in Amsterdam, they are trying to build a rocket to take them to a planet they are not even sure exists.

When I ask David about the nature of his role — about what needs to be done to get this wild journey back on track — he takes the rocket analogy and runs with it. “There are 100 million things that have to happen,” he says. “Many of them are quite mundane: recruitment, team dynamic, desk space. I don’t think these things are particularly interesting in themselves, but if we think of them as mechanical parts you need to build a rocket… everything has to be really well done, because we’re sending a rocket into space.” There is no room for imperfection, in other words. If one thing fails, so does everything else.

David admits this was his biggest challenge at Massive, and that once the studio headcount passed a certain point the to-do list became unmanageable. “But PlayerUnknown Productions is a small studio, so everything needing to be done, and everything needing to be great, is actually achievable. That’s incredibly exciting to the completionist gamer in me: oh my god, I can cross everything out! And then I can tell Brendan it’s done. We have our rocket.”

Of all the moving parts in play in the making of Prologue, Melba and Artemis, AI and machine learning feel like the most important. Yes, Prologue is a tech demo, a test balloon, a sampler — but it is nonetheless too big for human beings alone to make. Part of the reason Brendan has struggled with recruitment and team dynamics is that he is not really hiring for a game, not yet. It’s a research project: one that is not about making assets to plonk in a digital world, but about figuring out how to get machines to do it for you.

When he first arrived, David found the tech team talking with such fondness and familiarity for what he heard as ‘Emmel Agent’ that he assumed it was the name of an outsourcing partner, or a colleague working remotely. They were in fact saying ML Agent, referring to a collection of algorithms that have been fed enough relevant data to be able to perform staggeringly large volumes of complex tasks at impossibly high speed. It is at this point of the interview, I think, that my brain starts to come apart at the seams. David, bless him, assures me the same happened to him.

“Once you’ve educated an ML agent, it becomes a team member. It’s like having AI colleagues,” David says. “And that to me is mind-blowing. Will it work exactly as we think? It’s too early to tell. But I’ve already seen a lot of things that have been created by these new ML colleagues of mine that are just fantastic, honestly. It’s very hard for an old-school developer to believe. I said, ‘But what is the script?’ There is no script. ‘Who wrote the code? How do I modify it?’ There is no code. It’s created by an ML agent that has learned how to create this thing, and add it to the world.”

I ask for some examples, in the faint hope of getting my head around it. David gives me two. First up is animal behaviour. “You can populate a world with an incredibly large amount of animals, but they all need to have rules for how they behave. That takes a long, long time to write, especially if you want to have migration behaviours, and mating, and predators and so on. It’s really complicated to do by hand, but it’s an excellent task for an ML agent.”

The other is NPC AI, something Hit Points has written about in the past (and with which David very politely disagreed in a subsequent edition of MAILBAG). “If you write an AI enemy in a shooter, it’s basically just a reaction robot that has a set of fixed possible reactions,” he explains. “And because the human brain is clever, you can determine those states fairly quickly. Then you start playing against the pattern, rather than against the AI.” ML agents, however, can add vast amounts of nuance to the mix, and help create enemy AI that feels human. “Not like a superhuman, who always wins, but a human, with flaws and bad decisions and a lack of patience.” A singleplayer game, in other words, that feels like a multiplayer one? Right. Sure. There goes my brain again.

This is, needless to say, pretty advanced stuff, and it’s no surprise when Brendan tells me the studio has several patent applications under review. “We’ve created some new knowledge here: mapping terrain, populating it with trees and assets, inserting artist-made locations into that terrain — and that’s all done generatively, as you move through the world,” he says. “In Prologue now, you sit down and press Play and it generates a new, 64x64km map every time, populated and looking quite dense. But that creates a lot of challenges! If the world doesn’t exist until you step into it, how do you design for that? This is why we have a real research team. We have nuclear physicists and mathematicians and so on that are really doing serious work.”

When it arrives — Brendan won’t be drawn on timescales, recognising the scale of the task at hand — Prologue will be minimal in the extreme: you will be alone in the world, it will be cold, and you’ll have to find food, warmth and shelter. But it will be steadily added to over time, in a similar way to Brendan’s beloved Rust. And all the while PlayerUnknown Productions will be building towards Artemis, a planet-sized world in which an unprecedented number of players will be able to make their own fun: not just battle royales or survival games, but games of all kinds of style and genre, and even things that aren’t games at all. What Artemis eventually becomes is up to the people that choose to live, and play, and create there.

Brendan knows that he and the crew are in this for the long haul — he frequently refers to it as a ten- or 15-year project — and that machine learning is only part of the solution. If ML can’t speed up or improve a certain process, it won’t be used; if an existing thirdparty tool can do a certain job it will be integrated, and the engine is being designed such that it can incorporate any useful future technology that comes along. “We want to make our engine easy to mod, and to make it open source so everyone can participate. That’s what it has to be, I think. It won’t be PlayerUnknown’s Metaverse, just like it isn’t Tim Berners-Lee’s Internet. It has to be owned by everyone.”

Ah, there we go. Until now we have danced a little around one of 2022’s dirtiest words, but it is at last in the open. A vast, digital world, where people can play, hang out, and make things? Two years ago this would have sounded incredible, the stuff of far-off fantasy. But it is sullied, tainted even, by this year’s widespread corporate charge into the Metaverse, and the term’s inevitable association with blockchain, NFTs, and so many brands. Once again I wonder aloud whether Brendan is bothered by this; once again, he makes clear that he isn’t. “I’m just going to do what I’m going to do,” he says. “It’s this thing that we want to create, and it’s going to give people a lot of fun, a lot of pleasure, and a lot of meaningful things to do. But it doesn’t matter if it’s called the metaverse. I don’t care what people want to call it.”

Brendan has spoken in the past of his interest in blockchain as a technology, and while the evidence of the past 12 months might suggest it’s a flash in the pan, bigged up by hype merchants on the make before a seemingly irreversible collapse, he continues to see merit in the function of the technology, if not its execution so far. He is, after all, building a world in which people can make things; some record of ownership will be required, likewise some way for the community to monetise their creations.

“We’re building a digital place,” he says. “That has to have an economy, and it has to have systems at work. And I do believe you should be able to extract value from a digital place; it has to be like the internet, where you can do stuff that will earn you money. But it’s not about, like, Chanel and Louis Vuitton. It’s some kid called AwesomePickle selling cool skins because he understands what people want.” Blockchain might seem today like the most appropriate way for people to monetise the things they do in Artemis. But Brendan, David and company are still taking the first steps on a potentially 15-year journey. That is plenty of time for blockchain to turn into something that is not only useful but acceptable, beneficial even — or for some other technology to come along that does the job it purports to do in a better, more meaningful way, and renders it obsolete.

It’s unfortunate, really, that capitalism has caught up with Brendan’s vision while he’s been stuck in the weeds with it. But there is, I think, a pretty stark contrast between what PlayerUnknown Productions is trying to do and what, say, Mark Zuckerberg is trying to build at Meta. This is not intended to be a new way for brands to advertise to consumers, or to replace Zoom calls with a virtual conference room that looks like it was built in a beta version of PlayStation Home. It is not being built specifically around blockchain technology, NFTs, web3 or whatever the VCs are calling it this week. And as Brendan’s line about Berners-Lee makes clear, he is not building this for fame, or for money. (I suspect he has enough of both already.) The technology, eventually, will be open source. Ownership will be decentralised. “It’s for everyone, right? It shouldn’t ultimately be controlled by us,” he says. “It’ll be a platform that we participate in the maintenance of, maybe, but it’s something that anyone can plug into, and everyone can host a bit of themselves.

“I’m quite zealous about this. It has to be made a certain way. The only way this exists is if it’s made for everyone, and it’s not made for money.”

Suddenly, finally, my brain comes back online, and I realise what this is all about. Brendan made his name and (I assume) his fortune off the back of other people’s work, building on top of H1Z1 and ArmA, tooling around with the DayZ mod code. Is this not all just a very elaborate, ridiculously ambitious way of repaying the favour? Of making a way to let people find the same sort of success that Brendan has found, in an impossibly greater variety of ways?

“When you spend time at the studio,” David says, “you realise there is a genuine desire to give back. Once upon a time, Brendan was nobody, and then he discovered modding. And through modding, he became somebody. There is a real desire to give that opportunity to other people. And it’s not just Brendan: a lot of people at the studio say, ‘We want to find the next PlayerUnknown’. I think that’s really cool.”

So, can they pull it off? Honestly I have no idea. It sounds brain-meltingly ambitious, and the studio’s struggles to date suggest Brendan’s vision is, if anything, even harder to achieve than it sounds. Some enormous, established companies are betting hundreds of millions of dollars on their ability to beat him to his goal, or at least a version of it. And players are so hard to predict these days; it is impossible to know where the next breakout hit will come from, or what it will look like. I worry that by the time the team’s vision is ready for primetime, its audience will have moved on to other things.

But like David, I love dreamers, and I have not heard anything quite so dreamlike in years. I want developers to reach for the stars, to seek out the impossible, to give me ways to experience things I have never seen before. I have ridden enough horses, is what I suppose I am saying, and find the lure of a space rocket quite irresistible. I wish them all the best with it, and will be looking on with great interest. I hope you’ll do the same.

Thanks for reading! If this is your first time, Hit Points is a newsletter about videogames and the game industry, delivered twice a week to your email inbox. If you like the idea of fully independent, ad-free, SEO-ignorant journalism, you can sign up for free right now using the subscribe button below. Paid subs get access to additional posts, and my eternal adoration and respect, for just £4 a month.

To old hands, thanks for making it this far. Remember that shares are the lifeblood of Hit Points, and today of all days would be a great time to hit the button below as hard as you possibly can.

Have a grand few days, and I’ll see you in yer inbox on Friday.