#235: Machine killer

GenML's latest trick: an existential threat to online games media.

It’s been another one of those months in games media. Hell, it’s been one of those weeks: layoffs at Kotaku, a firing and solidarity walkout at The Escapist, the effective closure of Uppercut, and the founding of two new independent outlets, Aftermath and Second Wind. There are probably some more I’ve missed, and given the way things are going, there will be another couple by the time I’ve written this post. This is the way of things at the moment, and there’s been a version of today’s edition buzzing around in my head for months, waiting for a day when I had enough time and mental clarity to put it into words. I still have neither of those things, to be perfectly honest, but let’s give it a bash anyway, in order that I might finally be free of this mental burden. A problem shared, and all that.

The internet as we know it is dying, and the games media is a useful, albeit deeply dispiriting, lens through which to view the web’s decline. The rapid rise of generative machine learning — or GenAI, to use its wearyingly popular shorthand — is already transforming the internet, and is nowhere near finished. It has sent shockwaves through the media industry in particular, precisely because of how theoretically machine-replaceable a lot of its publishing output is, and the perilous nature of its finances. And the games media, which already has plenty of other struggles to contend with, is already firmly in the robots’ sights.

To understand what’s happening here, for the first and ideally last time in my life, I would like to talk about guides. What was once the domain of the fans — the true die-hards whose devotion to a particular game was so extreme that they would spend months of their lives putting together a charming ASCII-strewn text file breaking down a title’s every facet, and publishing it on GameFAQs — is today the very lifeblood of online games media. Guides are, for many outlets, the most reliable driver of search traffic, of ad impressions, and therefore of revenue. This is why one major website, which I shall not name as I don’t want to single anyone out, has published 160 — one hundred and sixty — guide articles about Tears Of The Kingdom. As is often pointed out, if writers were paid according to the revenue they generated, the guides teams would be on C-suite wages. Needless to say, they are not.

Guides are not fashionable; indeed, they are so unfashionable that hardly any gaming websites publish them on their front page, hiding them from their chronological feeds. But their importance to a videogame website cannot be overstated. Guides are the bubblegum summer blockbuster that funds the arthouse Oscar bait. If a website’s big-ticket reviews, longform investigations and airy, thoughtful features are the swan gliding along the water’s surface, reflecting the way an outlet wants to present itself to the world, then guides are the legs going like the clappers underneath, keeping the thing afloat. Guides, I am told, keep the lights on at some of the most prestigious, and popular, games websites on the planet, and at most of the smaller ones as well.

Thirteen years ago, when I got my start in games journalism by writing news for the Edge website, the main search-traffic battles were fought over games that were yet to be released. I attended one SEO presentation about how you could ‘win’ the search traffic for ‘[game name] review’ by making a sort of holding page with that term in the URL, filling it with whatever info on the game was available — trailers, release dates, rumours and so on — then optimising the crap out of it in a race to the top of the rankings. When, months or years later, the game actually came out and the website reviewed it, it would redirect the high-ranking holding page to the actual review. A vile, duplicitous business, sure, but I was told that it worked and that, hey, this was just the way the game had to be played. (Edge did not play it, which is just one of the many reasons its website no longer exists.)

Those battles are still raging today, on a wider scale than ever — I just Googled ‘The Witcher 4 release date’ and one of the results on the first page was from, and I promise I am not making this up, Cosmopolitan — but as I understand it, the focus nowadays is on search traffic for games that are already on the market. I suppose this makes sense: we play games for a lot longer now, whether because they are ever-evolving like Fortnite or Minecraft, or simply bloody enormous and complex, like Tears Of The Kingdom or Baldur’s Gate 3. The demand has therefore shifted from ‘when is this game coming out’ to finding out how to defeat a boss, optimise a dialogue exchange, solve a puzzle, complete a seasonal quest or find all of Collectible X in Region Y, and finding these things out via search is much quicker than scrolling through a 400-page text file on GameFAQs. I can totally see the logic in this. Reader interest in release dates, trailers and so on evaporates the day a game comes out, but guides can be relevant for years thereafter. Guides are, theoretically at least, evergreen, which has always been the online media’s holy grail.

They are also, quite often it must be said, bloody horrible things. I had a terrible time on Wordle the other day, and before I knew it I was on my final guess. While I was pretty sure I knew the solution, I wanted confirmation before I hit submit (please don’t judge me; I’m a couple of days away from my longest-ever streak). So off I went to Google, typed in ‘Wordle answer today’, and clicked the first link that came up. You can probably guess what comes next. The page was absolutely packed with bullshit unrelated to what I had searched for. It had little subheadings with answers to just about every potential Wordle search question under the sun: is Wordle getting harder? What’s the best starting word? Where did Wordle come from? Eventually, right at the end — after a few lines of hints, after Adblock had nuked 24 ads and I’d dismissed the pop-up request to enable desktop notifications — I got my answer. I was right, thank you for asking.

(Yes, yes, I use Adblock. It’s turned off by default, only ever turned on to deal with websites that have proven themselves to be unnavigable without it. Leave me alone.)

Not all guides are like this, mind you. I certainly appreciate that there is a craft to doing them well, and that the work required to assemble them from scratch is substantial. In the peak of my Destiny obsession I would always seek out Eurogamer’s guides, because they were cleanly presented and pleasingly direct, smartly employing a mix of video, text and still images in a bid to get me un-stuck on the game as quickly as possible. That’s the good stuff. That should be the rule, and in fairness, for many outlets it is.

Right, there’s some context. (Gosh this one’s going on a bit, isn’t it, sorry. Told you I’ve been thinking about it for a while.)

“Fuck this shit,” Techraptor CEO Rutledge Daugette — what a name, by the way — wrote on not-Twitter on Saturday alongside a screenshot of a Google search. “Thanks so much for taking our work.”

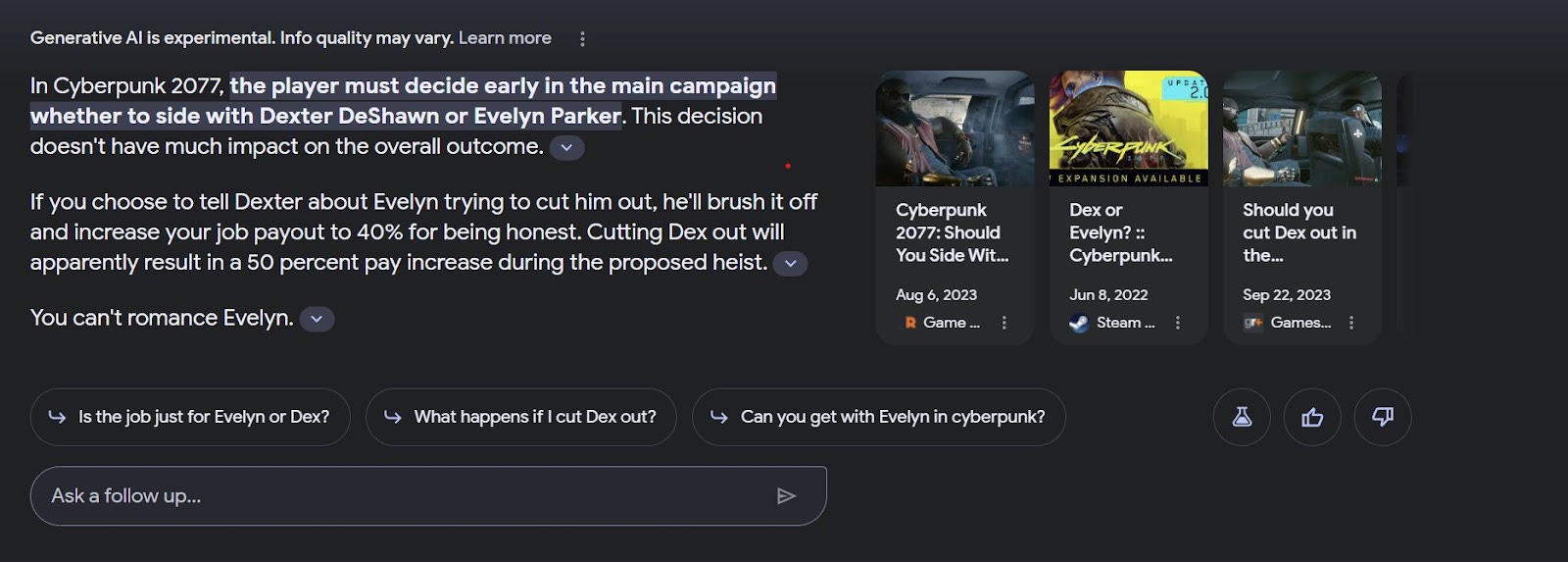

The target of Daugette’s ire is a new generative machine-learning feature Google is adding to search pages, which scrapes the top results and generates its own summary paragraph from them. It is a bit like the current snippet system, except since there’s no single source Google doesn’t have to link to any particular website, and there’s a box for follow-up questions where the source link used to be. It looks like this.

Google intends this to be an improvement, and in a very basic and really stupid way I suppose it is. It saves you a click, obviously. By taking in a range of sources I suppose it mitigates the risk of you getting the wrong answer to your query. And of course it strips out all the filler drivel that kept my Wordle answer from me the other day. But! It is, at the same time, extravagantly short-sighted, extremely cruel, and, well, just not very good. Google might think this a cleaner way of delivering search results, but it does so by overlooking that it was Google that made the mess in the first place.

Alex is right, of course. As I learned in those early SEO meetings, online media has little choice but to dance to Google’s tune, and it’s a bit rum of the company that is most to blame for the user-hostile clutter and bloat of today’s internet to suddenly go ‘hey, most search queries can be answered in a couple of sentences, let’s do that instead’. Particularly when doing so means depriving the website(s) that actually did the work your machine-learning tech is getting its information from of the traffic, and the ad revenue, that said content was specifically and solely produced to generate.

The implications of denying search traffic to websites that depend on it for revenue, I imagine, go without saying, but we’re 2,000 words deep into this thing already so we might as well get into it. This model may work for Google, and Google users, for games that are already on shelves. If someone searches for advice on Cyberpunk 2077’s Dex vs Evelyn decision in 20 years, Google’s ML models will be able to provide it. But what about the games of the future? What are you going to train the machine-learning models of tomorrow on when you’ve put all the guides teams out of work, the websites they used to write for have gone out of business, and no new ones have stepped into the void because you’ve shown there’s not a penny to be made from producing content for Google’s robot army to steal? Where’s the fucking future in that?

I’m not saying that this is the only reason the games media, or the internet, is on life support. But it’s a highly illustrative symptom of a wider malaise, I think, a useful model for understanding what’s going on here. Machine learning is certainly the last thing that online media workers need, given that they are already reckoning with a post-pandemic audience decline, the impact of the wider economic climate on ad budgets and affiliate spending, and an executive class that knows no way of responding to things being a bit challenging than hacking away at headcount, and has spent the last six months developing a progressively more raging stonker at the ‘efficiency potential’ of machine learning. I am not sure the ad-based business model was ever that sustainable, but it has never been in worse health than it is right now, as the global economy contracts, competition intensifies while headcounts dwindle, and machine learning emerges from the mist, knife clenched between its teeth.

There is a school of thought, often to be found in website comments sections and game journalists’ not-Twitter replies, that this is somehow justified; that online media has brought this reckoning upon itself by making today’s internet such an unpleasant experience. Websites that fill their pages with unblockable, unskippable, screen-occluding advertising. That bury the answers we seek beneath paragraphs of bland, link-stuffed, ruthlessly search-optimised text. That long ago put the needs of The Holy Algorithm ahead of those of their readers, and so have no right to complain that the machines have learned to cut out the middleman. Heck, as a veteran of print magazines — who spent his entire career being told his profession had been rendered irrelevant by 24/7 website newsdesks and always-online video creators, all giving their work away for free while I asked readers for six quid a month to tell them what happened five weeks ago — I probably have more reason than most to hang around online media’s gravestone, waiting for the crowd to thin so I can do a little dance on it.

But no. These people are my colleagues, my soldiers at arms. I have worked directly with many of them, spent time with many more on the events circuit. Against all the odds, I even like some of them personally. I believe that, despite everything, the overall standard of videogame journalism has improved tremendously over the years: the quality of criticism, the depth of investigative reporting, and the diversity of media mastheads have never been better. Besides, Hit Points would not exist without the hardworking newsdesks of, to name a few, VGC, Eurogamer, Gamesindustry.biz and The Verge. They break and report the news that I expand upon in a bit more detail (and at a lot more length). If these websites all suddenly went away, Hit Points would be dead within a fortnight.

If anything, my time in print makes me more sympathetic to the games media’s current plight, rather than less, because I have been down that hole myself and know how it feels. I know what it’s like to have management tell you your work isn’t profitable enough and that things need to improve while simultaneously hacking your team off at the knees. I know what it’s like to see your readership and team sizes decline because someone is offering a quicker and cheaper version of the work you’ve been doing for years. I know how miserable it is, and I also know there is very little you can do about it.

So, where do we go from here? I have my biases, admittedly, and they do not just come from my decade working in the (supposed) dying days of print. I grew up, and was privileged to later work, in an environment where the relationship between the games media and its audience was pretty direct, and based on trust: the reader handed over their money, and in exchange a talented team of journalists told them about a bunch of stuff they thought they ought to know about, in a way that they would enjoy. Today, across too much of the internet, those previously aligned incentives have been thrown completely out of whack.

Over the years the internet has developed an unkickable, highly debilitating addiction to advertising, cementing Google as the web’s most dominant force. Media executives long ago stopped caring about how high-quality or well-regarded their publications are, and focused solely on how well they monetise. Editorial teams must now divide their commissioning decisions between what they think their loyal readers will be interested in, and what Google Trends tells them drive-by readers are looking for, balancing their ever-dwindling resources between the work that they are passionate about and the work that pays the bills. Throughout there is the constant risk of a Google update killing their search rankings, an economic crisis tanking the ad economy, or a growth-at-all-costs exec team coming to their desk one morning with an axe. This is no way to make a living.

It seems pretty clear to me that the only way of putting all this right is by cutting all the evil entirely out of the picture — or, at least, to minimise its influence as much as possible. Alex Donaldson made the point this morning that sustainable revenue through search is absolutely achievable, genML notwithstanding, as long as expectations are kept in check and scale doesn’t get out of hand. That probably rules out corporate media, but suggests that indie websites, with realistic goals, can still make a living on Google’s internet. But my inner print dinosaur, ever the purist, reckons that the true future of journalism looks an awful lot like the past; writer and reader back in alignment, exchanging the former’s honest work for the latter’s money, their relationship freed of the fickle whims of the algorithm and the cruelty of corporate interference.

This was the bet I made, and the risk I took, when I launched an independent newsletter in the summer of 2021. Has it worked? Well, no, not really, subscribers are down this year, I’d rather not talk about it. But it is still early days, and I take comfort from the fact I now have company. Two years ago I was pretty much on my jacks with this thing; hardly anyone else was trying to make an independent living writing about videogames. Now I am merely a small and shrinking part of an ever-growing cottage industry of independent videogame media, of which Aftermath and Second Wind are merely the newest members.

I am not, after almost 3,000 words, about to turn this into a sales pitch — or, at least, not a sales pitch for Hit Points specifically. If I am trying to sell you on anything, dear reader, it’s a concept; a shift in mindset, an untangling of the hard-wired expectation that Good Internet Things should always be free. We’ve tried that, for decades now, and I think it’s time we tried something else.